Frequently Asked Questions

What is a realistic rate of weight loss? +

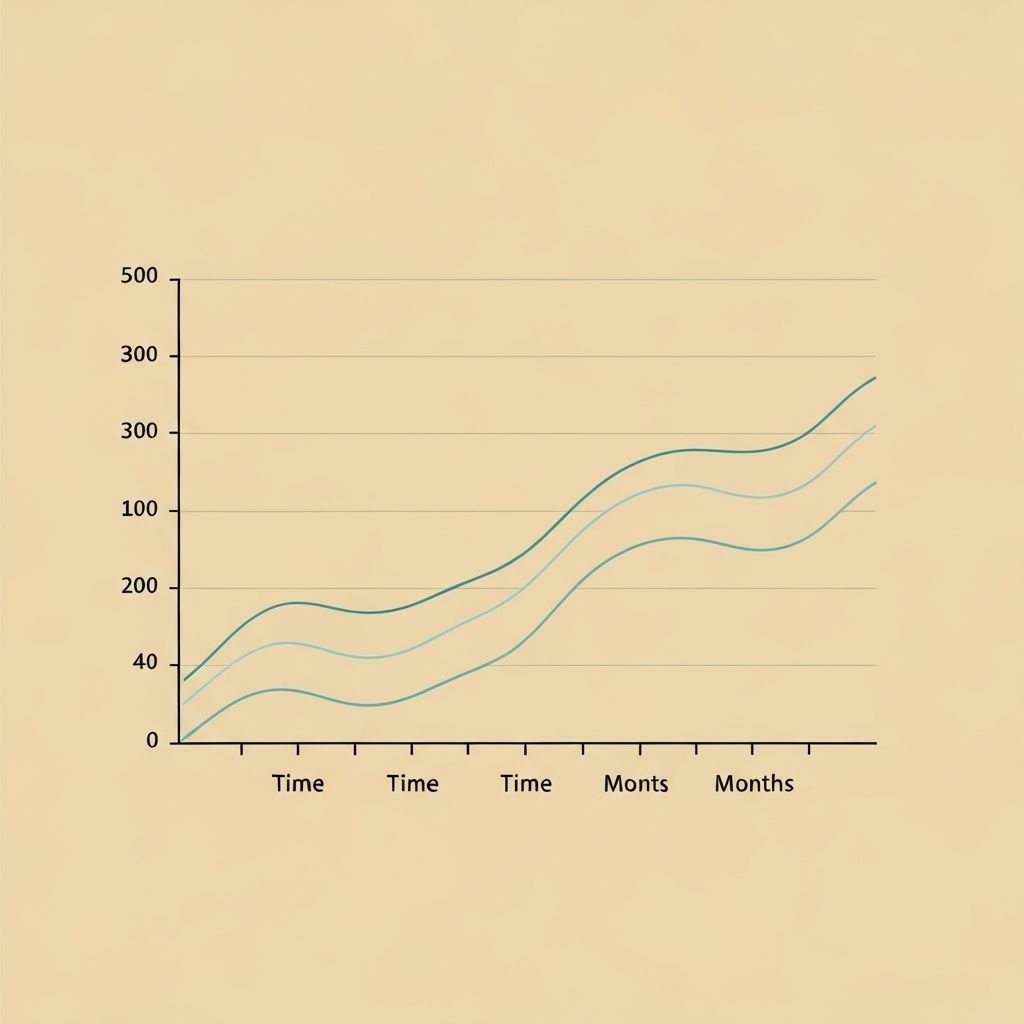

Research suggests sustainable fat loss rates of approximately 0.25–1% of body weight per week for most individuals. This varies based on age, sex, starting composition, genetics, and lifestyle factors. Initial weeks may show higher rates due to water loss, but true fat loss typically emerges after 2–4 weeks.

Why does weight loss slow down over time? +

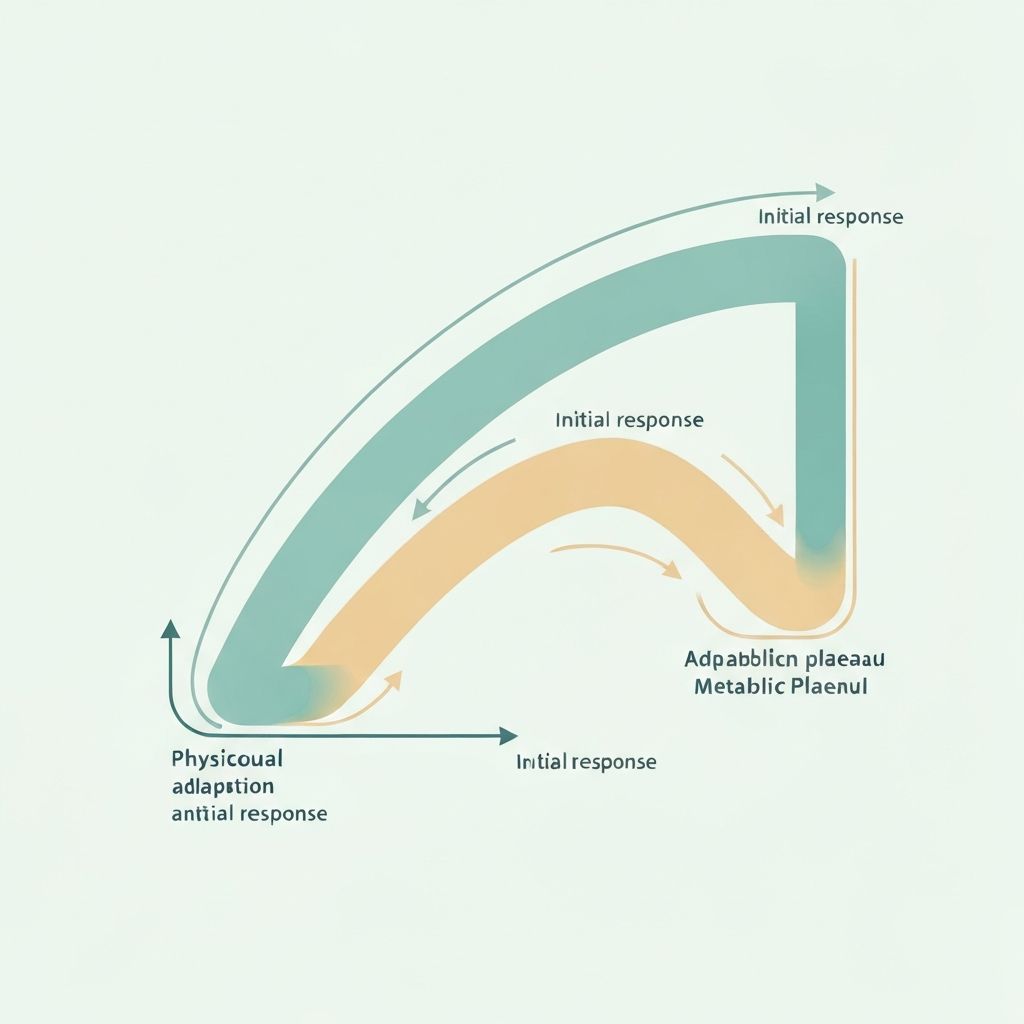

Multiple factors contribute: metabolic adaptation (reduced energy expenditure during sustained deficit), depletion of easy-to-mobilise water and glycogen stores, and potential compensatory changes in activity or intake. These are normal physiological responses, not evidence of failure.

What causes weight plateaus? +

Plateaus reflect a new energy balance equilibrium where intake and expenditure have adjusted relative to each other. Continued deficit requires further changes to intake or activity. Plateaus are also masked by short-term water fluctuations masking underlying fat loss.

How much of weight loss is water vs fat? +

Initial loss (first 1–2 weeks) is predominantly water and glycogen. After that, the proportion shifts toward fat loss as water stores stabilise. However, water fluctuations continue throughout due to diet, hormones, activity, and stress—making short-term scale changes poor indicators of fat loss.

Do individual differences in weight loss rate matter? +

Yes, significantly. Age, sex, starting body composition, genetics, metabolic history, and lifestyle factors create wide variation in response to identical energy deficits. This variation is biological, not behavioural—it does not reflect effort or adherence differences.

What is metabolic adaptation? +

During sustained energy deficit, the body reduces metabolic rate through hormonal and neurological adjustments, partly to preserve lean tissue and maintain essential functions. This is an evolved survival mechanism. It makes continued deficit require greater effort but is not permanent.

Why is the scale weight not a complete picture? +

Scale weight includes fat, muscle, water, glycogen, food residue, and other tissues. Changes in any of these affect scale weight independent of fat loss. Water and glycogen fluctuations alone can create 2–3 kg variations daily, masking true fat loss patterns.

How do goal-setting approaches affect long-term success? +

Research suggests process-oriented goals (focus on behaviours) tend to support longer-term adherence and psychological resilience compared to rigid outcome-focused goals. Flexible approaches that emphasise controllable processes show better long-term engagement.

What factors predict long-term adherence? +

Self-efficacy, intrinsic motivation, process focus, social support, and self-compassion are strong predictors of sustained engagement. Rigid goal-setting and external motivation alone are weaker predictors of long-term maintenance.

Where can I learn more about this topic? +

Explore the detailed articles linked on this site under "Realistic Change Explorations" or visit academic databases such as PubMed for peer-reviewed research on energy balance, metabolic adaptation, and behaviour change. Always consult qualified professionals for individual guidance.